Eero Saarinen's objective was simple: he wanted to “clear up the slum of legs” underneath tables and chairs. An astute and critical design mind, Eero went through extensive research, revisions and scale-modeling to achieve his goal, only to conclude that the solution to the design problem was simplicity itself. The result is Saarinen’s Pedestal Collection designed for Knoll in 1958: a visually pure, sculptural and timeless collection that can be found in the inspired interiors of then and now.

The Roots of Modernism

Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus on the powerful idea that the fusion of art, architecture and industry could be applied towards a social good. The school – repeatedly upended by political and wartime upheaval across Europe – opened its doors in 1919 and closed them in 1933. During this short period, the roots of Modernism were established by the pioneering designers who dared to push the limits of material, form and function in architecture, textile and object design.

The Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany.

At the same time, Walter Knoll, a furniture maker in Stuttgart, Germany, provided furniture for the 1927 Weissenhof Siedlung exhibition featuring buildings by Mies, Gropius, Peter Behrens and Le Corbusier – all leading Modernists of the period. His son, Hans, sought to bring the Modernist vision championed by the Bauhaus masters to America, establishing H.G. Knoll Furniture Company in 1938 as an importer of modern furniture.

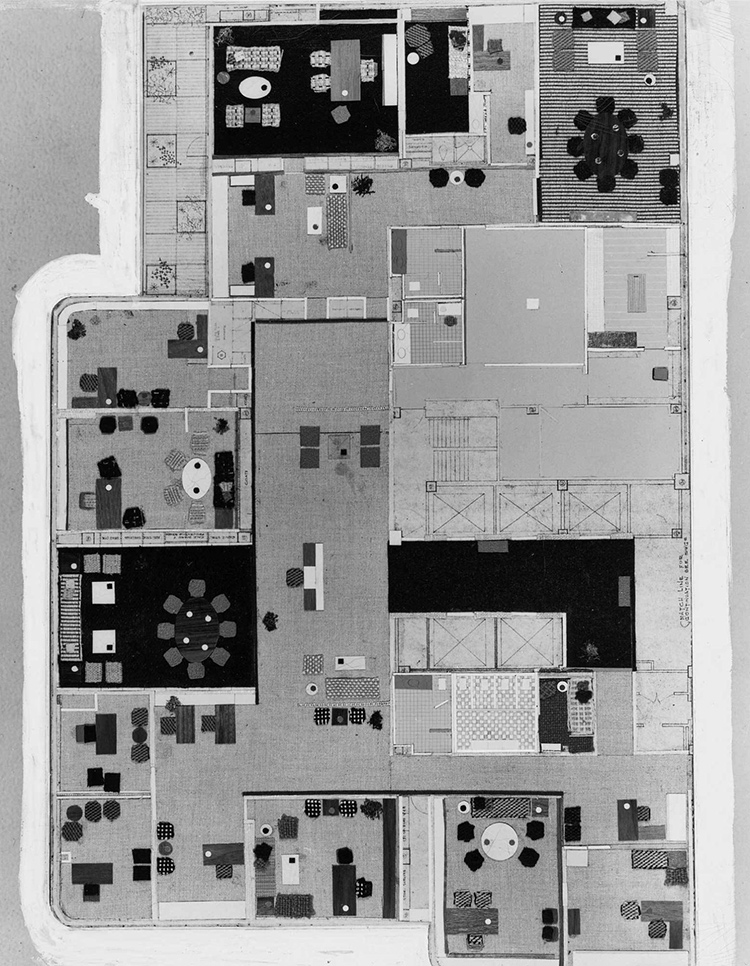

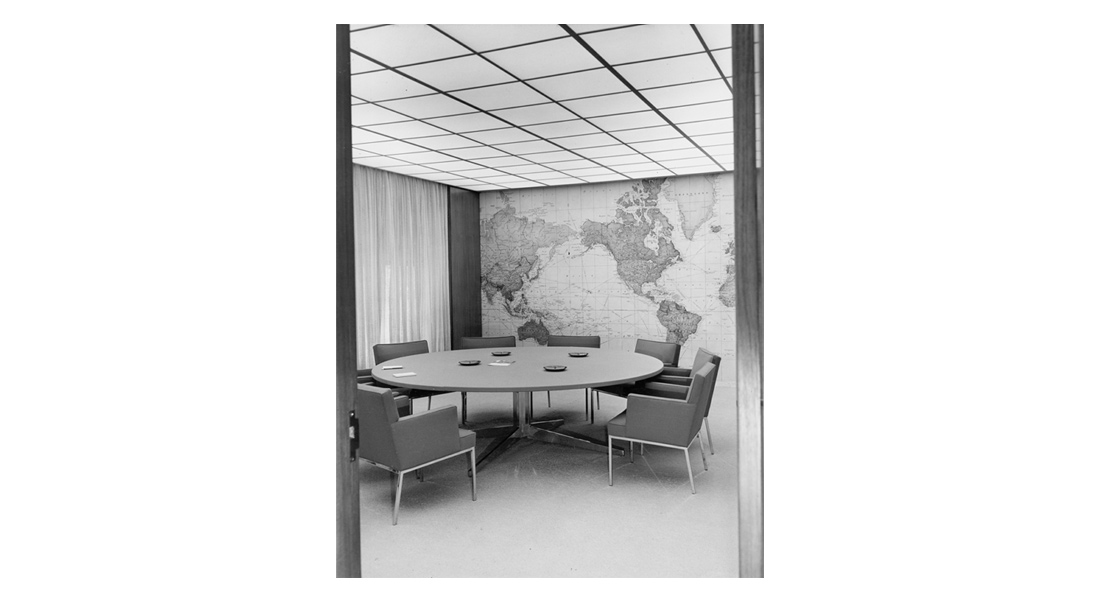

Ultimately, Knoll’s strong ideological ties to the Bauhaus revolve around Florence Knoll. She was mentored by Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology and later worked under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. The final director of the school, Mies brought the concept of gesamkunstwerk – the total work of art – from the Bauhaus to IIT. Greatly influenced by Mies’ teachings, Shu translated the idea of “total design” to the Knoll Planning Unit. With the Planning Unit, she completed large corporate projects and placed Knoll furniture in architectural spaces to create inspiring, Modern work environments that defined the post-war American interior.

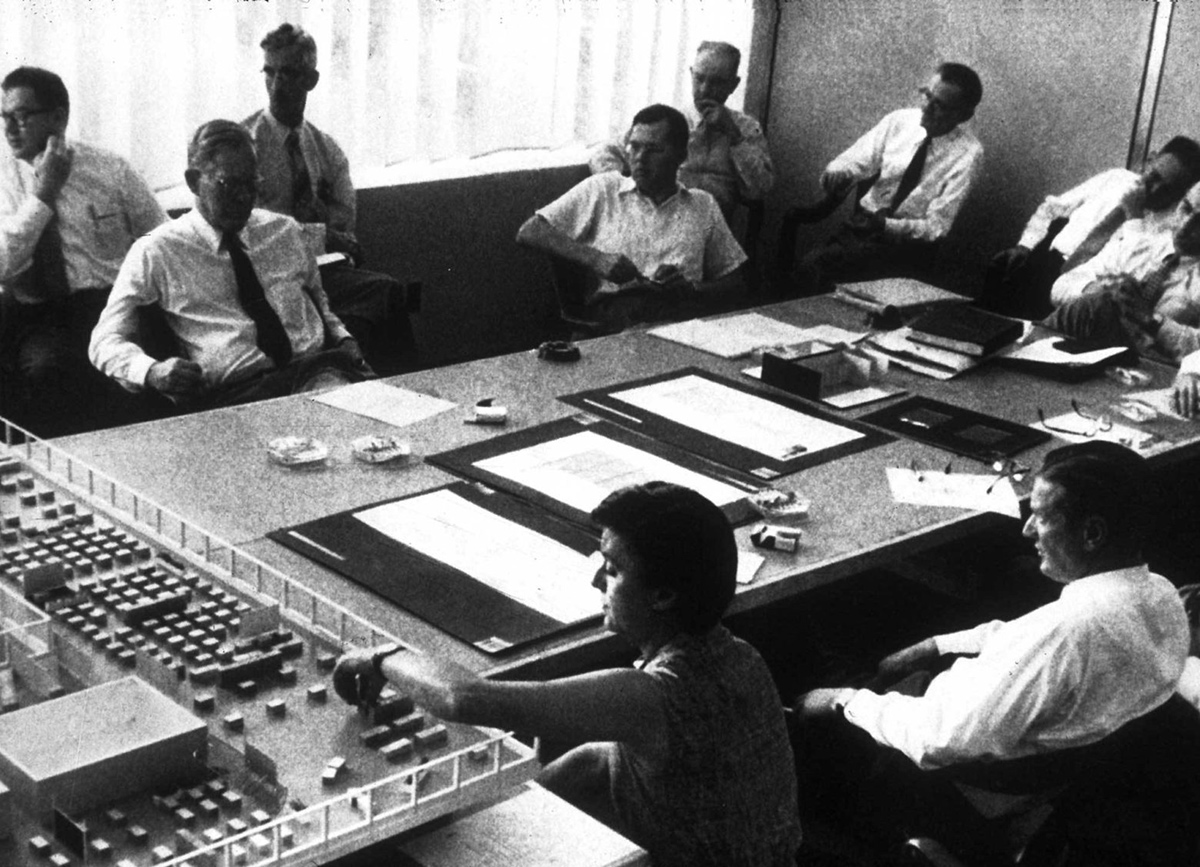

Florence Knoll delivers a Knoll Planning Unit proposal for the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (1951).

In this sense, Knoll is founded upon the idea that furniture design is only valuable insofar as it contributes to and speaks to the “total design” of a space. Even the furniture Shu designed herself was envisioned as part of a spatial whole – she referred her pieces as the “meat and potatoes” that needed to be designed as solutions to larger problems. In her embrace of the Bauhaus principle of the total work of art, she helped define American Modernism and set a precedent for design that is holistic rather than object-focused.

In honor of the centennial, Knoll revisits the Bauhaus alumni who mentored Florence Knoll and underscore our guiding principles.

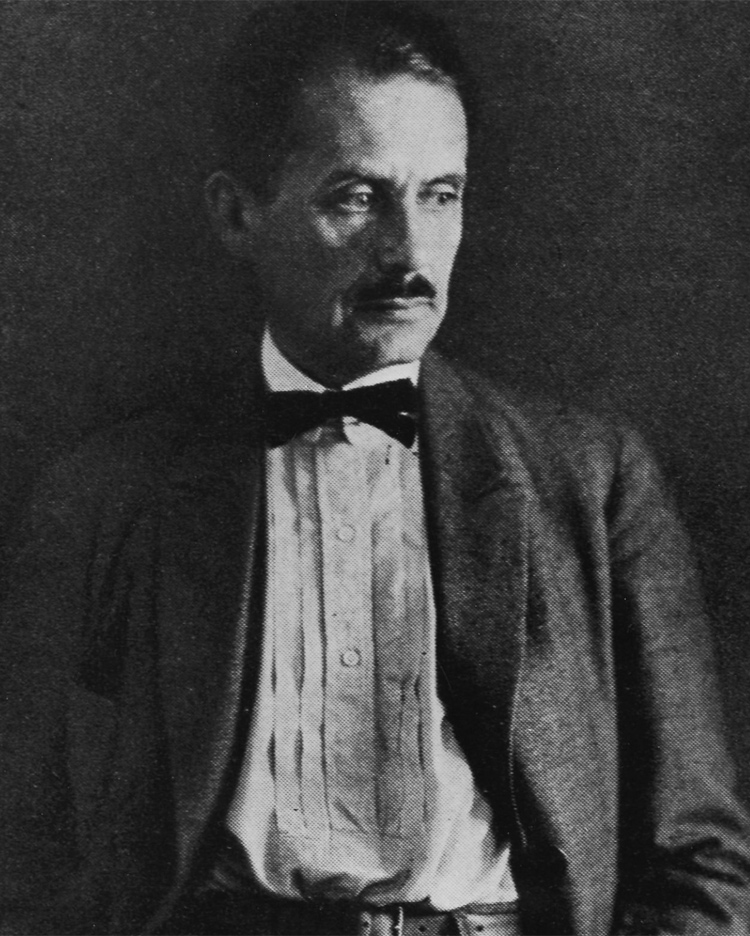

Walter Gropius: A Leader in Design Education

Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus School in 1919. Previously an active member of the Deutscher Werkbund, Gropius conceived the Bauhaus as an institution to fuse the fields art, design and industry in order to elevate social order and mass production. He encouraged students at the Bauhaus to collaborate, innovate and push the boundaries of material, form and function while establishing the roots of Modernism in Europe.

Due to rising political tensions, the Bauhaus was forced out of Weimar in 1923. Gropius designed and built new facilities in Dessau, Germany that is considered among Gropius’ highest achievements. The building’s design epitomized the rational and functionalist principles upon which the Bauhaus was founded.

Like many of the leading Modernists in Europe, Gropius sought refuge from World War II. He moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts to teach at Harvard University and establish his own practice alongside fellow Bauhaus designer Marcel Breuer. In Cambridge, he and Breuer mentored a young Florence Knoll.

Marcel Breuer: A Pioneer in Material Innovation

A champion of the Modern movement and protégé of Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer is equally celebrated for his achievements in architecture and furniture. His work embodies the driving objective of the Bauhaus to reconcile art and industry.

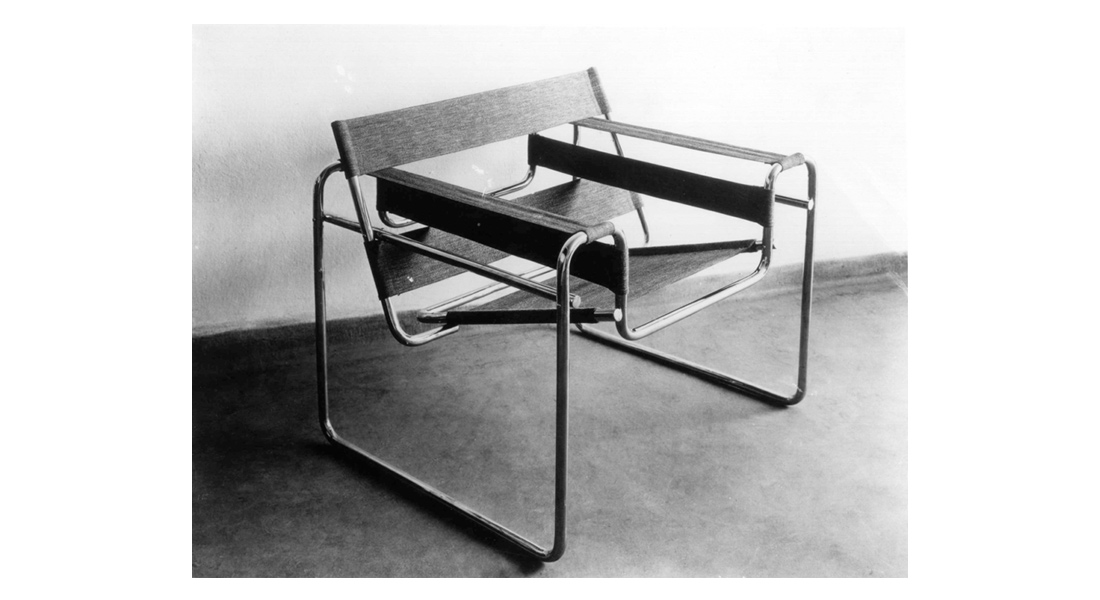

While a student at the Bauhaus, Breuer revolutionized the modern interior with his experiments in material. He was the first designer to use tubular steel in his furniture designs after becoming inspired by the construction of his own bicycle. The designs – now known as the Wassily Chair and Laccio Tables – remain among the most identifiable icons of the modern furniture movement.

In 1923, Breuer provided furniture for Haus am Horn, a prototype for affordable, mass-produced housing designed by Bauhaus architects Georg Muche and Adolf Meyer. The project is an early example of rationalist spatial planning and exhibited modular furniture pieces.

When Breuer immigrated to the United States, his attention moved towards architecture. He worked with Walter Gropius in Cambridge and independently in New York City. In 1969, Knoll introduced the Breuer Collection as part of its acquisition of the Gavina Group.

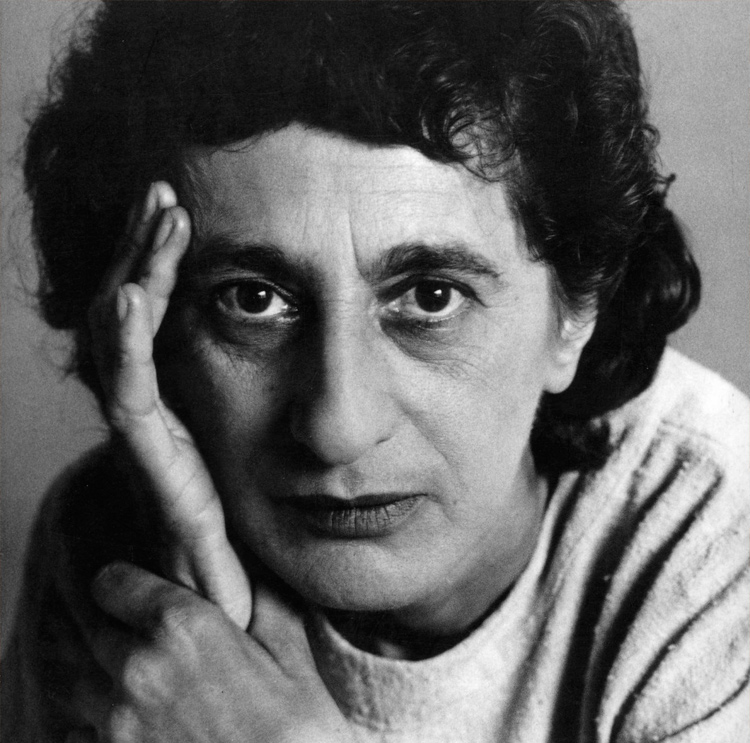

Anni Albers: An Innovator in Modern Weaving

Anni Albers is one of the most influential textile designers of the twentieth century and a leader of the Modern weaving movement. In 1922, she began studying under Gunta Stölzl at the Bauhaus. Her studies culminated with a highly regarded abstract wallcovering made of cotton and cellophane. She remained teaching and experimenting at the Bauhaus as head of the weaving department until the school’s closure in 1933.

At the invitation of architect Philip Johnson, Anni and her husband, painter Josef Albers, moved to North Carolina to teach at the newly founded experimental art school, Black Mountain College. In 1949, the Museum of Modern Art mounted an acclaimed one-woman show featuring Albers’ designs, cementing her status as a prolific artist and master weaver.

Florence Knoll invited Albers to collaborate with KnollTextiles in 1951, resulting in a thirty-year relationship between the two. Albers brought her stylistic point-of-view to Knoll, helping to direct and define the company’s ever-evolving identity. She debuted her best-known pattern, Eclat, in 1976. The design exemplifies Albers’ philosophy – to ground designs in order, but not in an overly apparent manner.

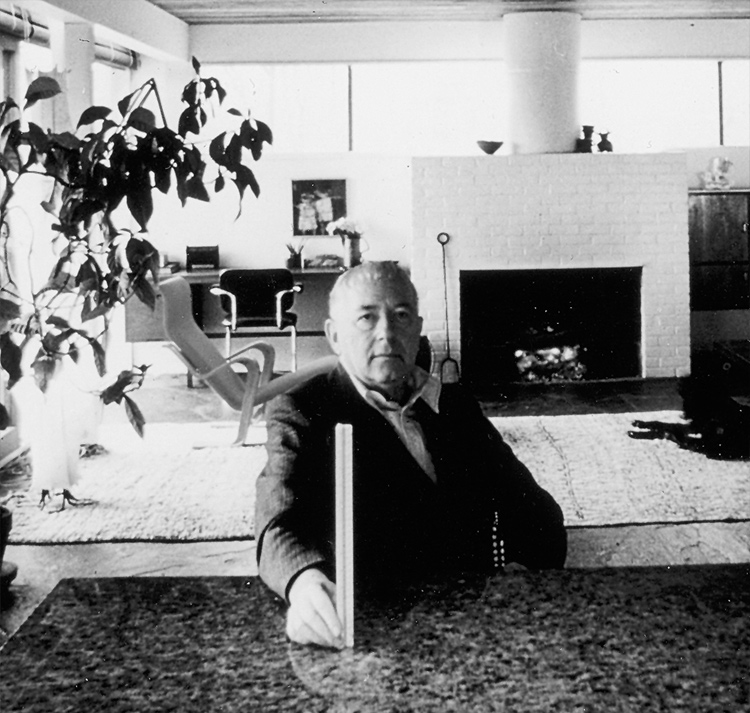

Mies van der Rohe: A Leader in Modern Architecture

Among the more ubiquitous figures of the Modern movement, Mies van der Rohe borders on the mythic in the world of architecture. His ‘less-is-more’ approach to design became the golden standard for many generations of architecture to come.

Mies earned recognition in Germany by imagining Modernist skyscrapers of steel and glass, leading to commissions for private residences such as Haus Lange and Vila Tugendhat. In 1929, he and Lilly Reich designed the German Pavilion for the Industrial Exposition in Barcelona. The pavilion debuted site-specific chairs for the King and Queen of Spain – the Barcelona Chairs – and is widely considered a defining moment in the shape of Modernism.

Mies was the third and final director of the Bauhaus, leading the school until its closure in 1933. Three years later, he accepted an invitation from the Illinois Institute of Technology. In his book about Mies, Philip Johnson pointed out his precise manner of incorporating furniture into an overall design, demonstrating his core belief in the total work of art. “No other contemporary architect cares so much about placing furniture,” wrote Johnson. This belief in “total design” with an exacting attention-to-detail in the placement of furniture in architectural spaces greatly influenced Florence Knoll, who studied under Mies at IIT.

Florence Knoll: A Trailblazer in Spatial Planning

Florence Knoll founded the Knoll Planning Unit in 1946, setting the standard for the Modern corporate interior of post-war America. Influenced by Mies, she introduced the ideas of efficiency, spatial planning and comprehensive design to workplace interiors. Shu had an exacting eye for detail and ensured that the execution of each project lived up to her concept. She ardently maintained that she did not decorate space – she created it.

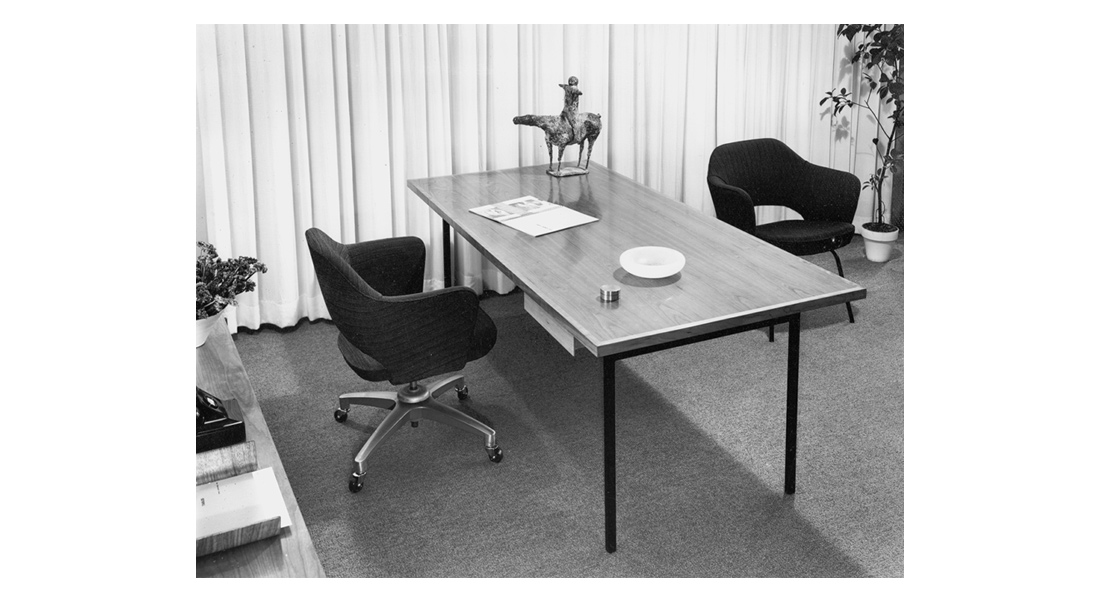

Florence Knoll’s capabilities were not limited to the highly-regarded Planning Unit. She designed some of Knoll’s most iconic pieces of furniture. Responding to direct needs she encountered while working on projects, Florence Knoll designed seating, tables and case goods. Clear and concise in both message and appearance, her work demonstrates how elegantly she defined modern and how she continues to influence the Knoll commitment to inspired workplace interiors today.

Hans Knoll's office in the Knoll showroom (1951).

Hans Knoll's office in the Knoll showroom (1951).

Florence Knoll Table Desk and Lounge Chairs.

Florence Knoll Table Desk and Lounge Chairs.

Florence Knoll Table Desk.

Florence Knoll Table Desk.

Florence Knoll Parallel Bar Series Lounge Chair.

Florence Knoll Parallel Bar Series Lounge Chair.

Marcel Breuer Wassily Chair and Laccio Tables.

Marcel Breuer Wassily Chair and Laccio Tables.

Mies van der Rohe MR Collection and Brno Chair.

Mies van der Rohe MR Collection and Brno Chair.

Marcel Breuer Wassily Chair.

Marcel Breuer Wassily Chair.