Features

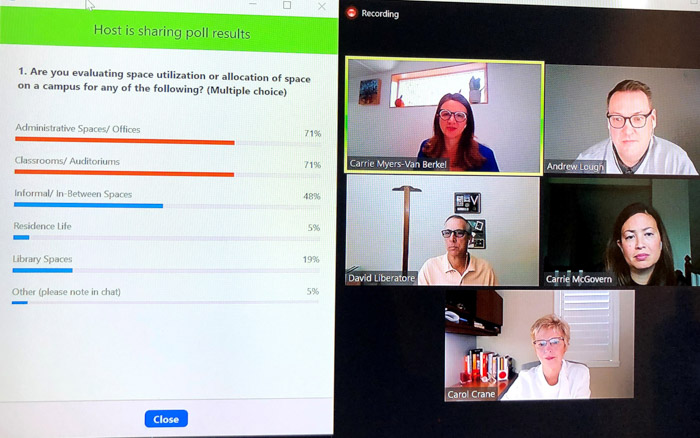

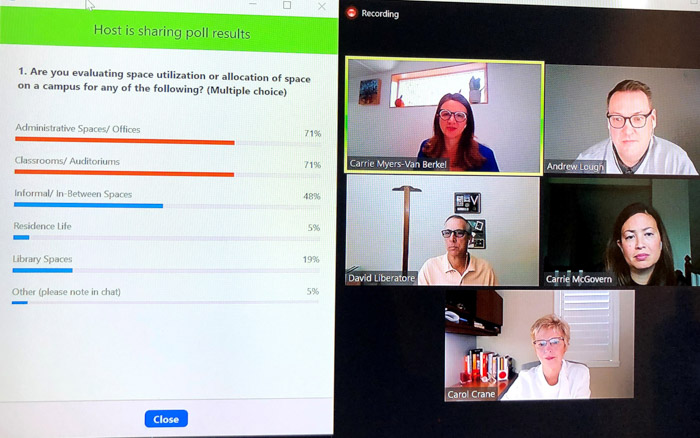

Knoll Hosts Panel on Higher Education with BSA LifeStructures

Panelists discussed new Knoll research, Connected Campus

Knoll Education recently convened a panel with BSA LifeStructures, an Indianapolis-based national design firm focused on higher education, healthcare and research clients. The panel discussed challenges and opportunities in colleges and university design and planning, and explored ideas in Knoll’s recent research paper, the Connected Campus, developed in partnership with Elliot Felix of brightspot Strategy.

Carol Crane, Vice President Education and Healthcare, Knoll, moderated a panel comprised of David Liberatore, BSA Learning Practice Director; Carrie McGovern, BSA Senior Interior Designer; Andrew Lough, BSA Senior Facility Planner and Carrie Myers-Van Berkel, Knoll Manager Education | Healthcare.

Explore the key takeaways below.

1. Implementing evidence-based design at pre- and post-occupancy stages contributes to a better outcome

While evidence-based methodologies are commonplace in the healthcare market, the approach is less utilized in the higher ed market, where it could better inform design.

“We know students are stressed and have anxiety. And 75% of students are saying that virtual only doesn’t work for them,” said David Liberatore. “It’s important that we find ways to use these evidence-based methodologies.”

Panelists agreed that engaging early in the process was vital. “We want to really understand what we’re looking for, what data are we trying to find, what those drivers might be,” described Carrie Myers-Van Berkel, Knoll.

In many cases, it’s a matter of leveraging information the institution already has, which is even more important as facility people at universities continue to be squeezed and are being asked to do even more, noted Andrew Lough. “We have to utilize some of the things that they already do. They already do student satisfaction surveys. A lot of that is around their educational experiences, but part of the questionnaire is about their satisfaction with space. And we need to use that to help measure some of these components.”

Panelists also mentioned that utilization metrics described in the Connected Campus, and in particular, examples of how community colleges and business schools more fully utilize their spaces, also provide a useful tool in discussions.

Evidence-based design is also seen as an important tool to use in attraction and retention efforts, particularly in an era of declining enrollments.

“We do see the population bubble coming down for students that will be going through universities in the future,” said Lough. “So we should ask: What metrics can help with retention? What spaces help them feel rooted in that university? And before that, how do you get them in the door? What attributes are going to help draw them in for that particular program?”

2. Spaces need to flex more than ever

Panelists agreed that COVID has shifted the way spaces are used today and will be going forward.

“We have to evaluate spaces in multiple different ways, from how spaces are being used during the pandemic and how they will be used in whatever the new normal is,” Lough explained, which also illustrates an important point about flexibility.

Gone are days of dedicated subject-specific classroom,” he said. “Today classrooms have to do multiple duties and accommodate multiple functionalities. How does that flexible model classroom integrate with the high flex model of learning – hybrid – in class and remote class? How do you integrate the technology into those spaces to allow that?”

It also illustrates planning challenges of the faculty office. “Every conversation is so personal, it is their space on campus, and is attached to a staff person or faculty member,” Lough noted.

Panelists concurred on seeing a trend toward more efficient use of office space, shrinking the size of faculty offices and going to more open workstations. However, the struggle in academia is often less about having the practicality of an office and more about it being a status symbol and a way of recognizing tenure or achievement for the faculty. Solutions vary depending on how tight space is on a particular campus, as well as the particular academic discipline, panelists postulated.

“The push has been to maximize space utilization. It does account for a lot of space on campus, from 25-to 30% for most institutions,” Lough noted. “That’s a huge amount of real estate that has a relatively low utilization rate. Using the 40 hours a week utilization model, you may get 40 or 50% utilization. But using the expanded 7-day model described in the Connected Campus, it’s even lower utilized. How do we maximize that? How do we find the balance between COVID, dedicated separate space versus more utilized touchdown spaces and hot desking applications?”

McGovern offered that faculty offices may be less affected by Covid and more about a culture that rewards achievement and length of tenure.

What may be a timely discussion is one about more creative ways to show recognition rather than reward with real estate, such as an art wall that recognizes achievement that a Durham research organization installed. With many institutions experiencing success with partial or full work-from-home programs, portending potentially fewer staff and faculty onsite, such alternative methods of recognition may have their moment.

Another way to incentivize change is to ask users to choose between more spacious offices or an alternative, such as more robust amenities, increased shared spaces or premium laboratory facilities. The latter is a strategy the Stanford School of Medicine uses often to get scientists “on board” with the concept of a smaller office footprint, according to Carol Crane, Knoll.

Nevertheless, panelists acknowledged academia’s a slow-to-change-culture and that it may take another generation to implement significant change to faculty offices.

3. Lifecycle costs should be factored into planning discussion

Because project budgets are not generally set by those who need to execute the plan and design, it’s vital to educate clients on the importance of lifecycle costs.

“We do our best to educate them as to the importance of lifecycle costs and to think about things holistically. But the project budget is still what it is and it’s not going to shift. It’s about education,” noted Carrie McGovern.

Forming partnerships early in the process can pay dividends as all parties have an interest in selecting products that will perform in the long run.

Added Lough, “The holistic piece about creating partnership is not just between architect and institution. It's with contractor and the construction manager who ideally is on board before design phase starts. And it’s about communication, partnership all the way through. They're invested in long-term relationship with client as well. So, they don’t want to go with a cheaper product or cheaper solution that’s not going perform over time.”

Holistic also relates to building systems as well as individual components.

“We’re seeing more and more holistic design requests with inclusion of furniture, equipment procurement, installation and management into the model,” explained Lough, who added that it’s designers who are increasingly bringing in holistic costing model. “We’re being asked to do more and more because they have less staff to manage throughout the process.”

Panelists also discussed the challenges of trying to measure furniture and other aspects of interiors.

“Using a lifecycle / holistic approach came into our world with energy and sustainability and materials first because of LEED,” related Liberatore. “One of reasons it works for energy is because there’s a simple way to see and track and measure it. But we don't have the same dashboard for success of furniture and material.”

“Maybe we as designers should be creating dashboards for our owners to measure success of design. Not just how beautiful it is how does it make them feel? Where’s the efficiency of operation? Because if they cut corners on furniture, do they have to replace it in five years, rather than getting 10 years out of it?” Liberatore proposed.

“It’s ultimately about giving quality. They need to be able to measure quality, and we don't give them the tools,” Liberatore added. Panelists agreed providing such measurement tools would help justify investing upfront in a premium product.

Panelists also discussed partnering with furniture manufacturers for tools and techniques to gather data for decision-making, including visioning sessions, surveys, and in-person observations.

“It always comes back to research,” said McGovern. “Clients want more proof. It’s very common in healthcare, not as much in higher ed, but is growing. We always like to have the ability to provide some statistics and data to clients. It can be hard to convince them about softer side of design and importance of that.”

“The research component of what furniture industry does is hugely important,” agreed Lough. “There are lots of great papers. That helps illustrate and brings together those points that help inform conversation we’re having with clients.”

Partnerships and research will help with the holistic approach with clients.

“Owners tend to think of design as this shell we’re going create and we’ll bring in furniture afterwards,” described Liberatore. “If you’re doing a holistic approach, it shouldn't be that way. It should be part of concept, both an interior and exterior solution.

“We need to find those connection points and make clients aware of them so they know it needs to be integrated solution, not just, ‘We’ll get this nice design and we’ll go get the cheapest furniture we can because that’s all we can afford.’ It’s not going to be successful if that student sitting in the chair is uncomfortable. They’re going to be dissatisfied with the space,” Liberatore emphasized. “User satisfaction is what this is about.”