When Yves Vidal became the president of Knoll International in 1951, he inherited a company that had only recently upended the traditional idea of a furniture showroom. Under the direction of Florence Knoll, Knoll showrooms around the world were arranged as tableaus of habitable environments, a setup that was both confusing and alluring to visitors. At the Paris outpost, where Vidal first joined the company, the bewilderment was even more intensely felt.

When Yves Vidal became the president of Knoll International in 1951, he inherited a company that had only recently upended the traditional idea of a furniture showroom. Under the direction of Florence Knoll, Knoll showrooms around the world were arranged as tableaus of habitable environments, a setup that was both confusing and alluring to visitors. At the Paris outpost, where Vidal first joined the company, the bewilderment was even more intensely felt.

“It was very strange because most people did not understand at all what we were selling,” Vidal recalled to Knoll historians in the late 1970s. “For the first time, furniture was shown in position, which means not all the chairs together and all the tables together. It was grouped together like an office or living room with flowers and plants, and people were looking at it and didn’t understand at all what we were selling. They were saying, ‘What do you think they sell.’ Most of the answers were, I am sure, ‘They are florists.’ All they could see were the flowers and the plants. They couldn’t realize we were selling furniture.”

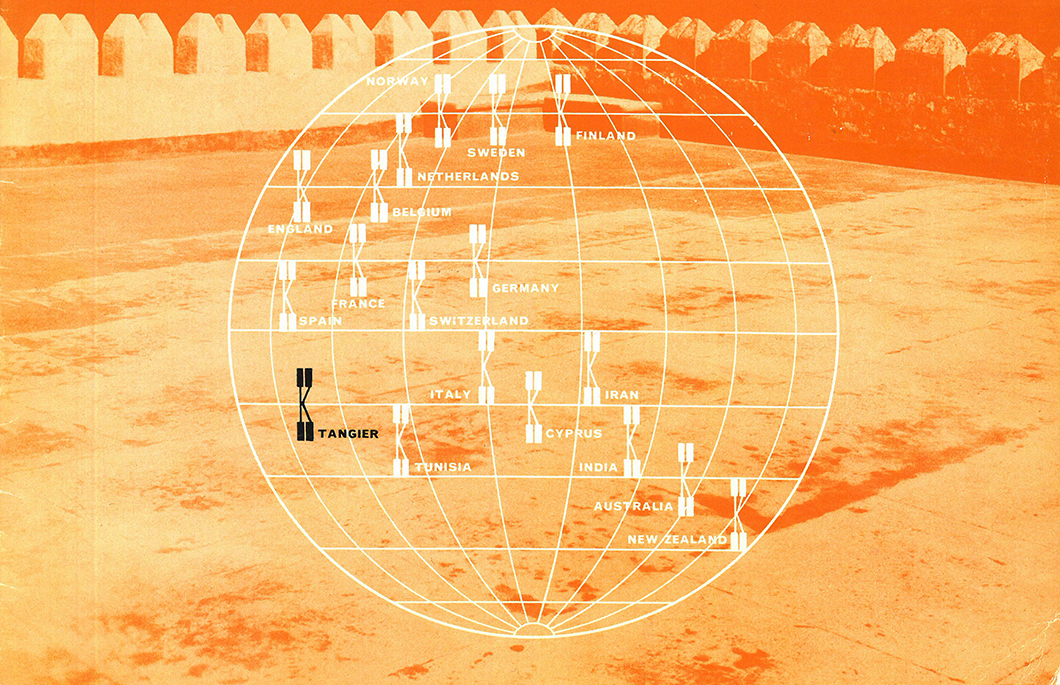

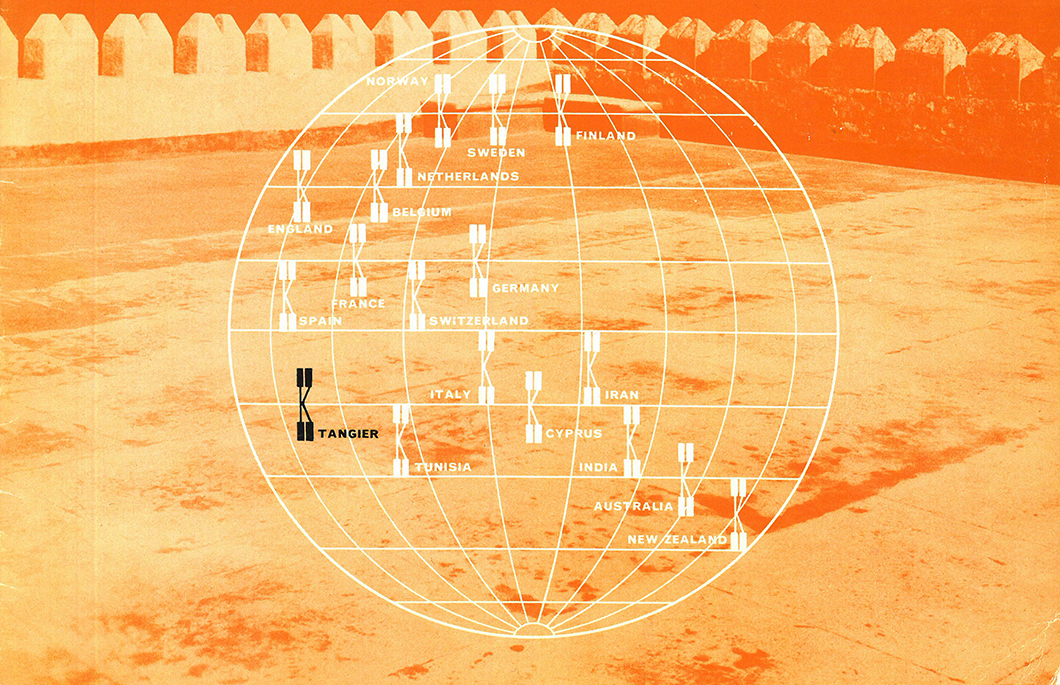

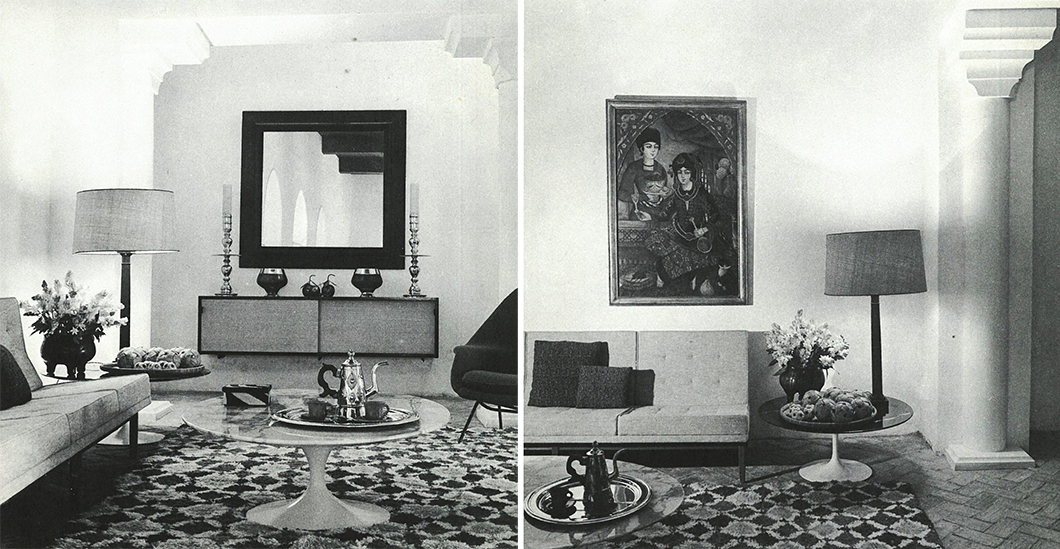

A Knoll International Brochure documenting Yves Vidal's York Castle.

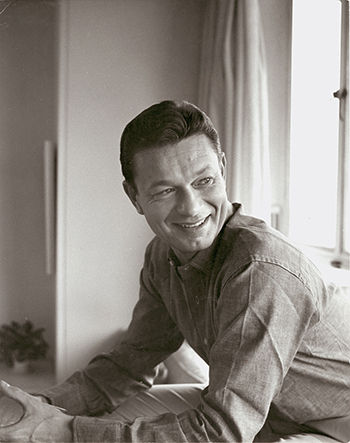

Nevertheless, the carefully arranged, albeit unprecedented, vignettes of Knoll showrooms quickly became well-known for their refreshing methods of product presentation. But when Yves Vidal purchased York Castle, a crumbling fortress in the cosmopolitan Moroccan city of Tangier, he found the ultimate stage set for his company’s modernist catalog.

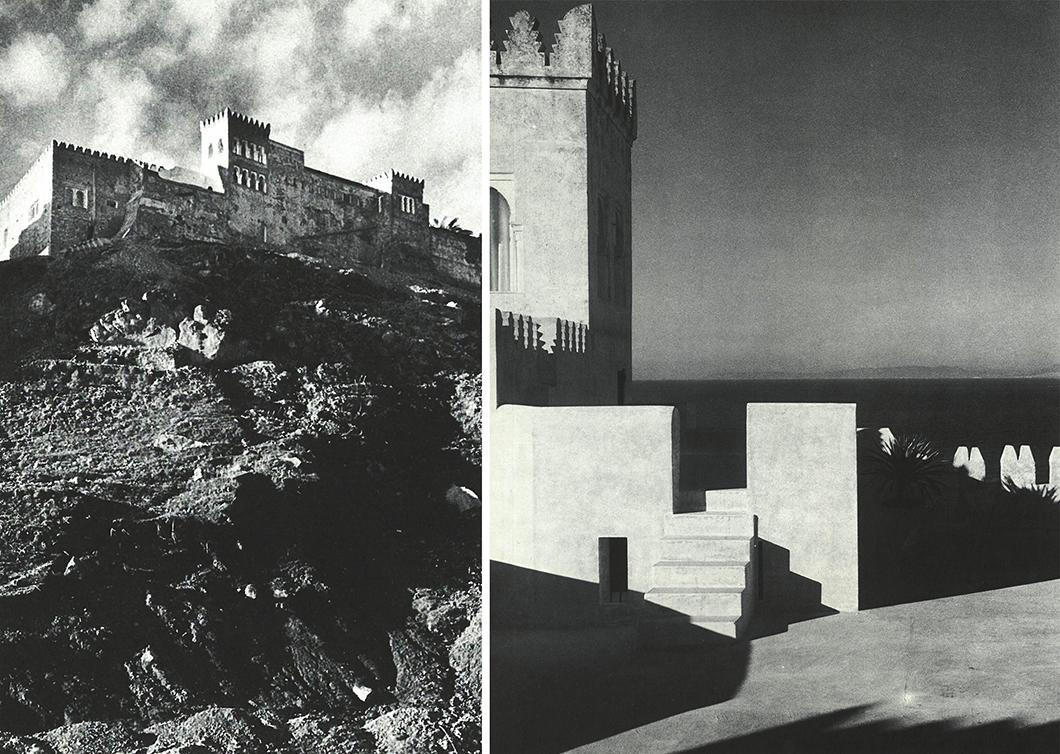

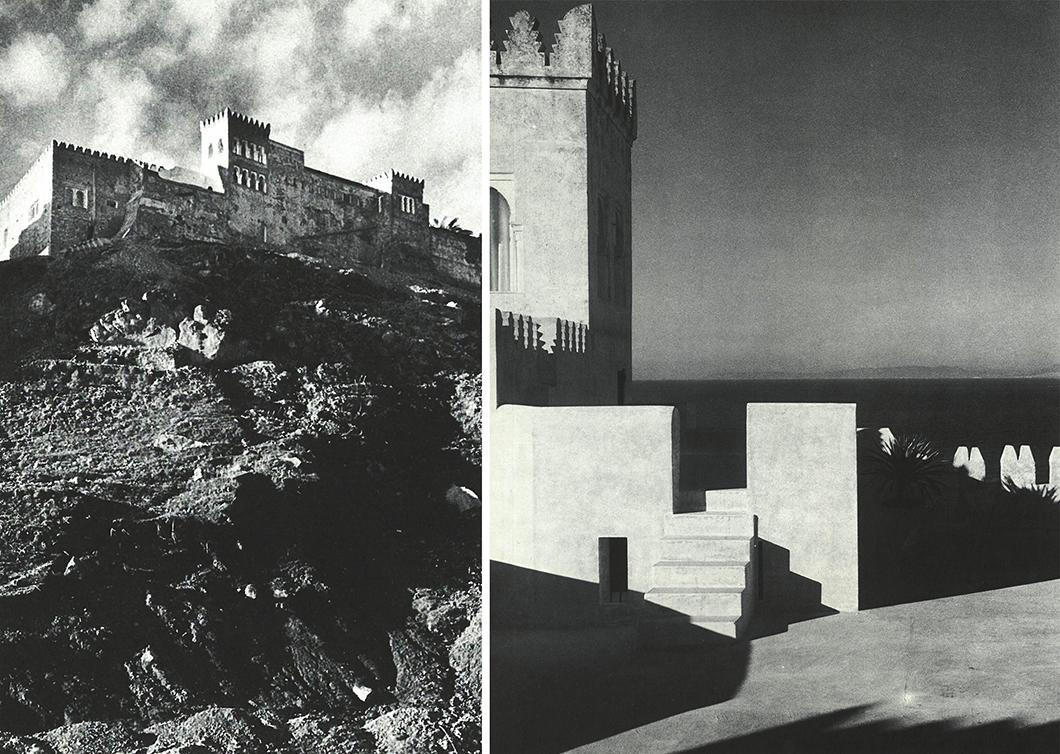

York Castle, with its crenellated rampart walls, was situated above the beach on the edge of Tangier.

Built by the Portuguese in the 16th century, the picturesque fortress off the Strait of Gibraltar went through many lives before coming into Vidal’s hands. Named after the British Duke of York who once served as the governor of Tangier, the castle was positioned on the edge of the Casbah, the dense, labyrinthine center of the old city. Later, it was rebuilt for the commanding general of the Moors, transformed into a garrison, then a prison, and even became a stable for the horses and elephants of a Moroccan Sultan. After a tumultuous history, York Castle was left empty and decrepit by the beginning of the 20th century.

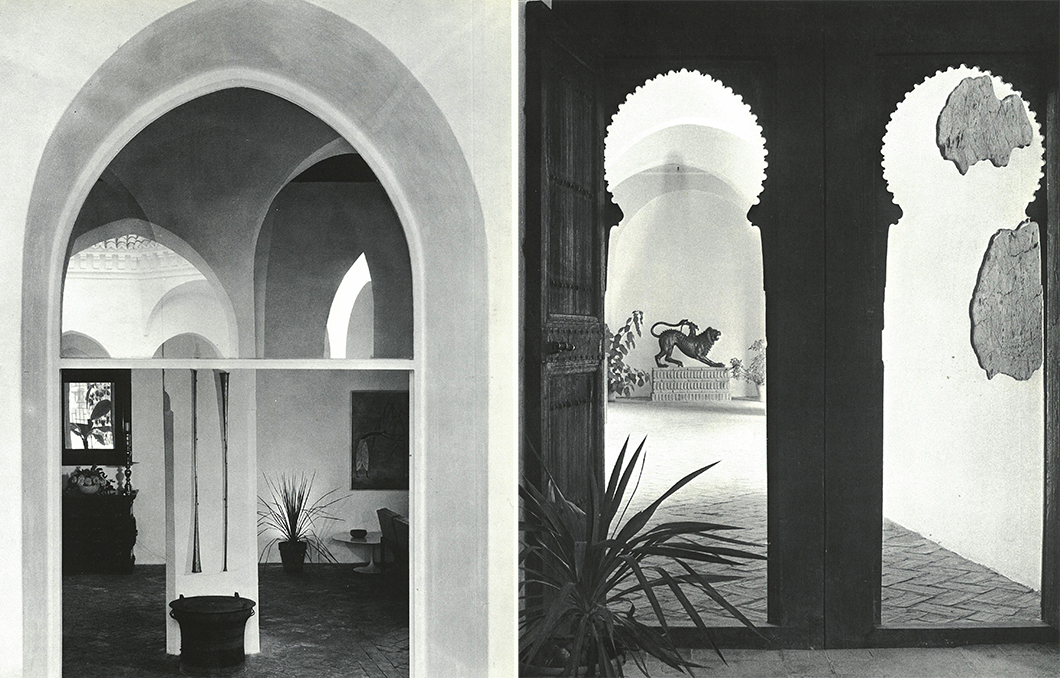

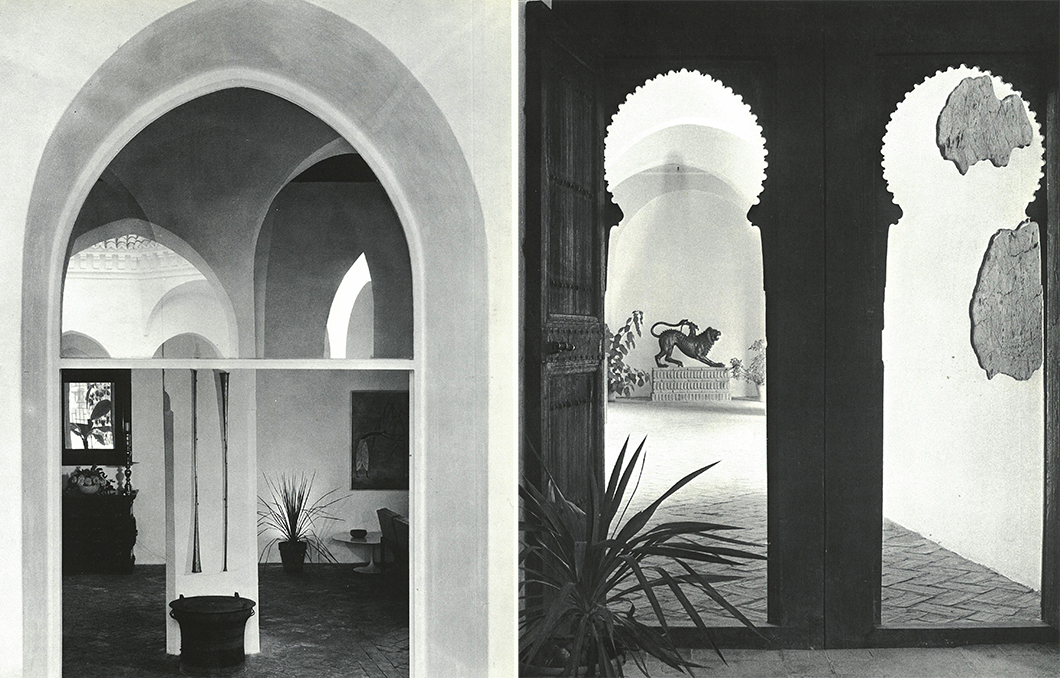

Yves Vidal filled the rooms and courtyards of York Castle with artifacts of African, Middle Eastern, and Asian origin.

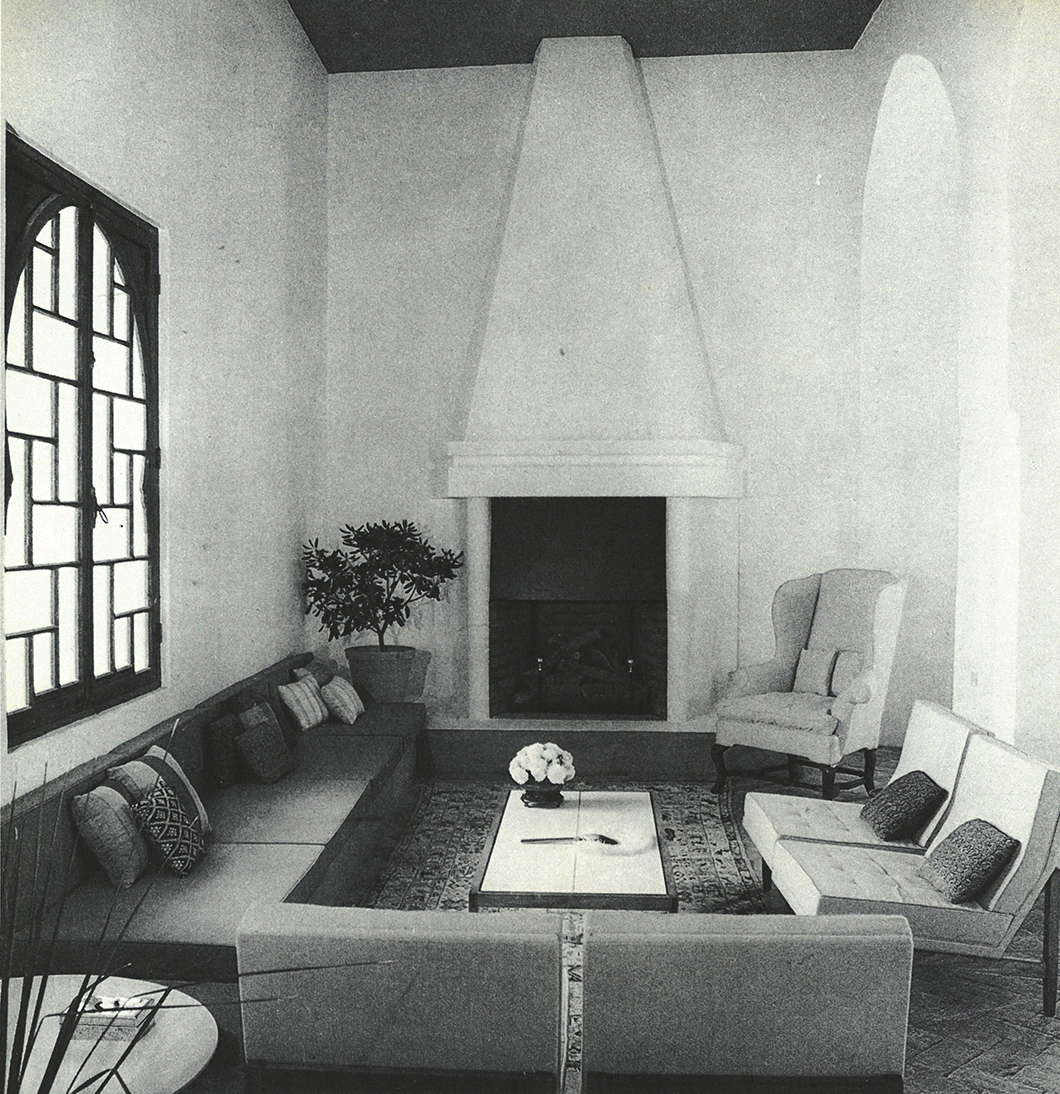

When Vidal took over York Castle in 1961, he saw in the medieval ruins a matchless setting for the clean lines of contemporary furniture design. With the aid of his partner, interior designer Charles Sevigny, along with Belgian architect Robert Gerofi, Vidal set about refurbishing the immense residence, restoring its roof and walls, retiling its floors and remaking its terraces. The team sought to maintain the Moroccan idiom that had defined the structure for the past 300 years, using terra cotta red ceilings and whitewashed walls, filling the entryways and arches with traditional patterned grills and colored doors of local origin. In certain places, fragments of the original walls were left visible beneath the newly laid plaster, bearing 17th-century inscriptions by Christian prisoners once held captive in the fortress by Barbary pirates.

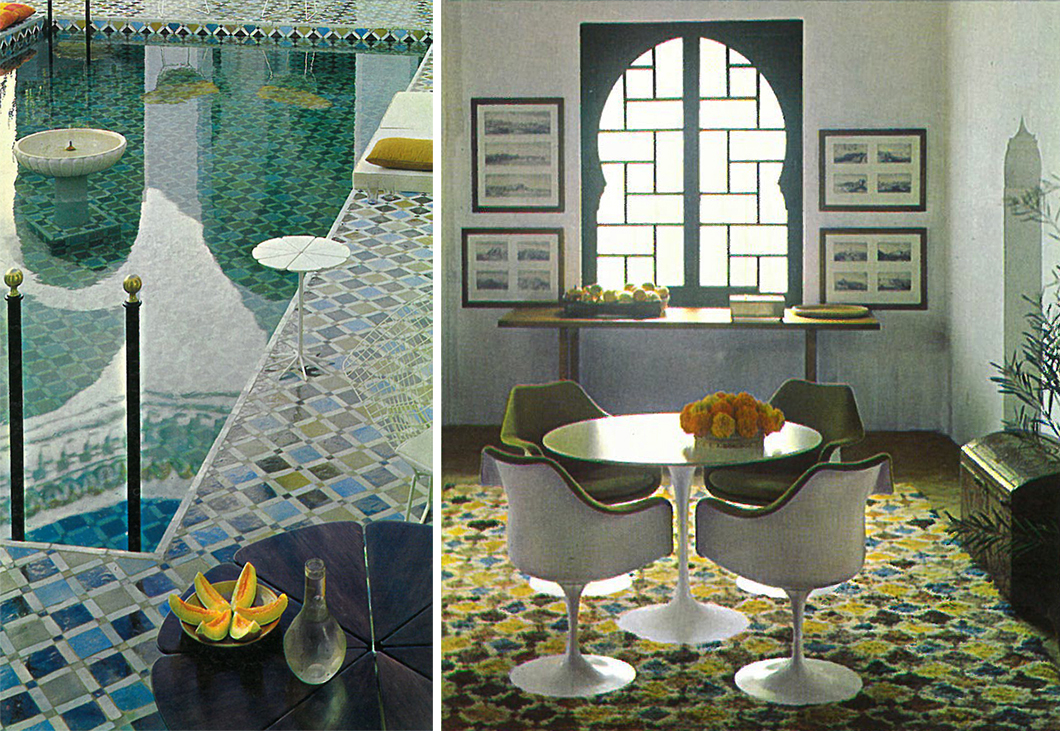

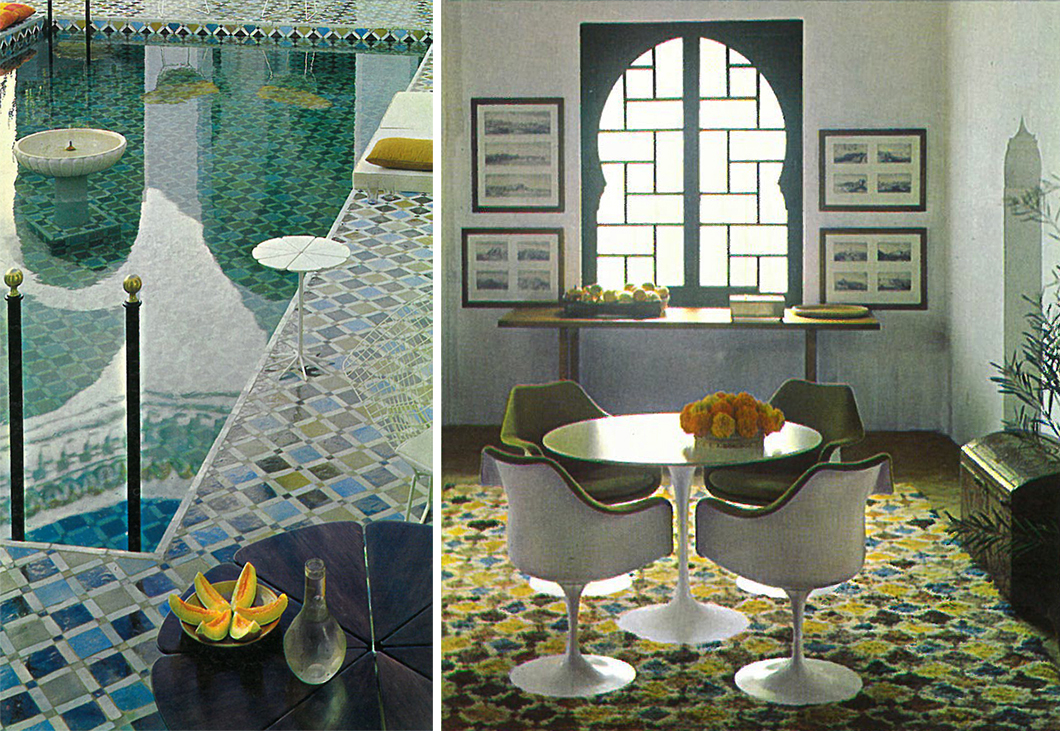

The central courtyard of York Castle contained a swimming pool with a stone fountain at its center.

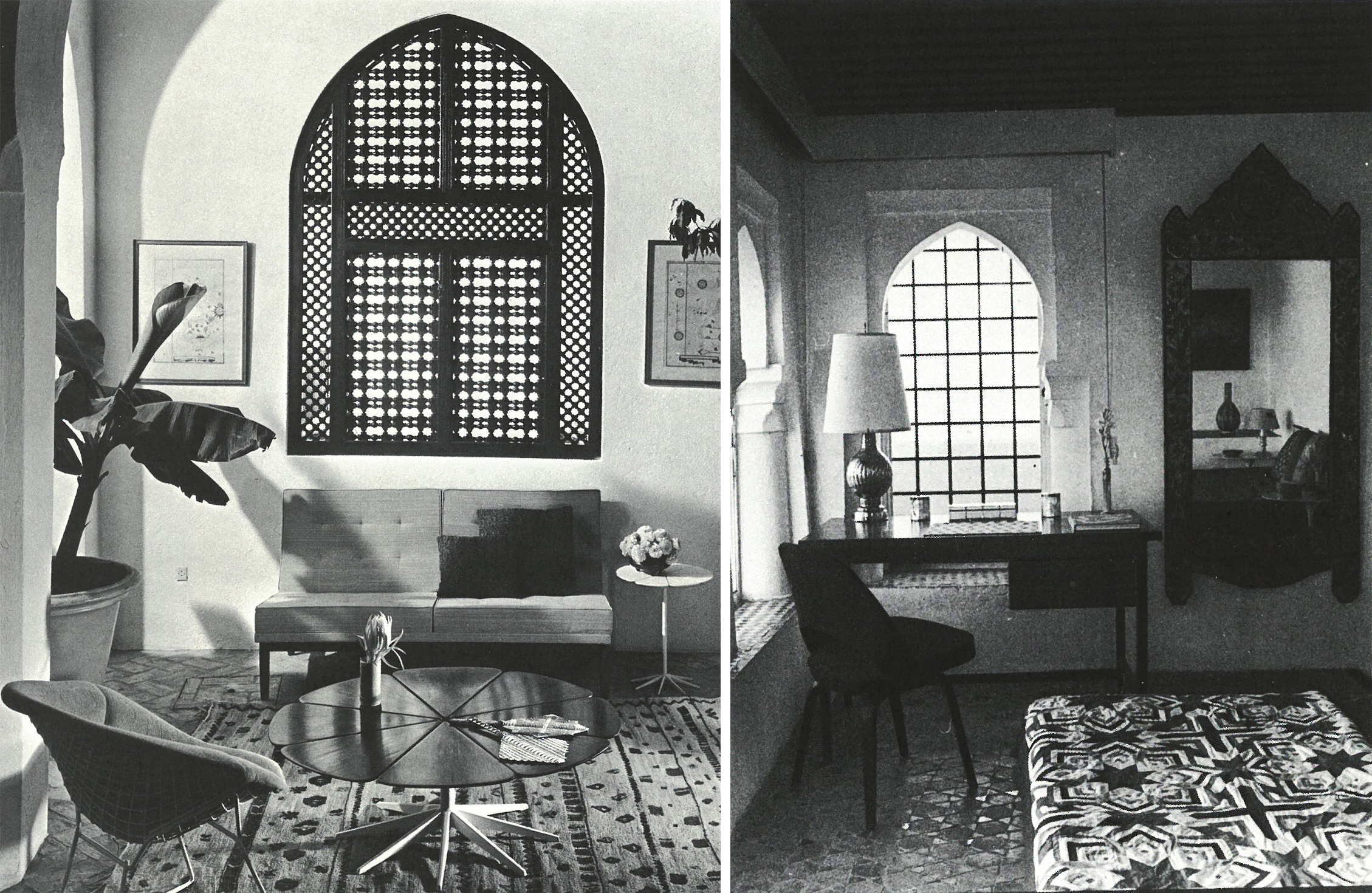

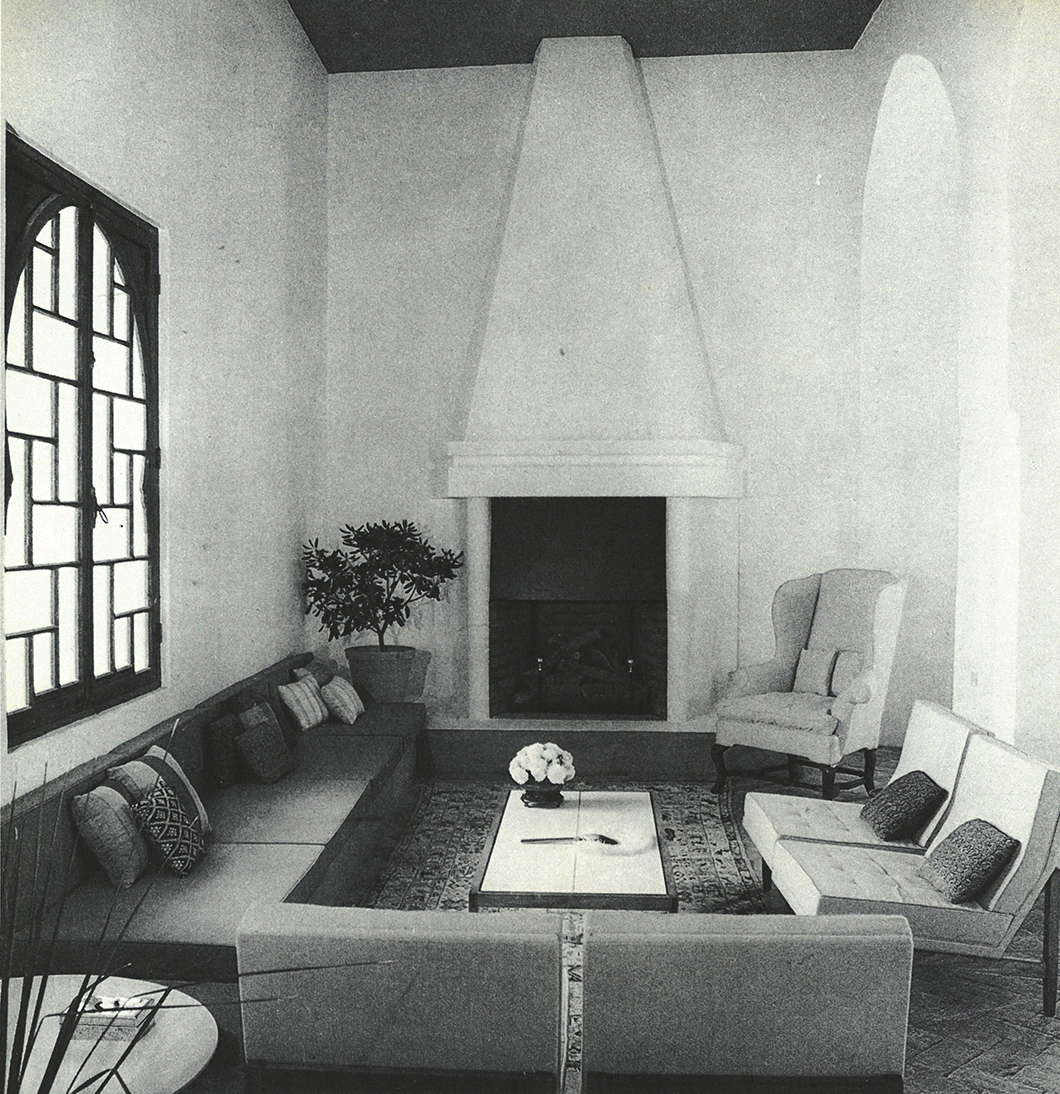

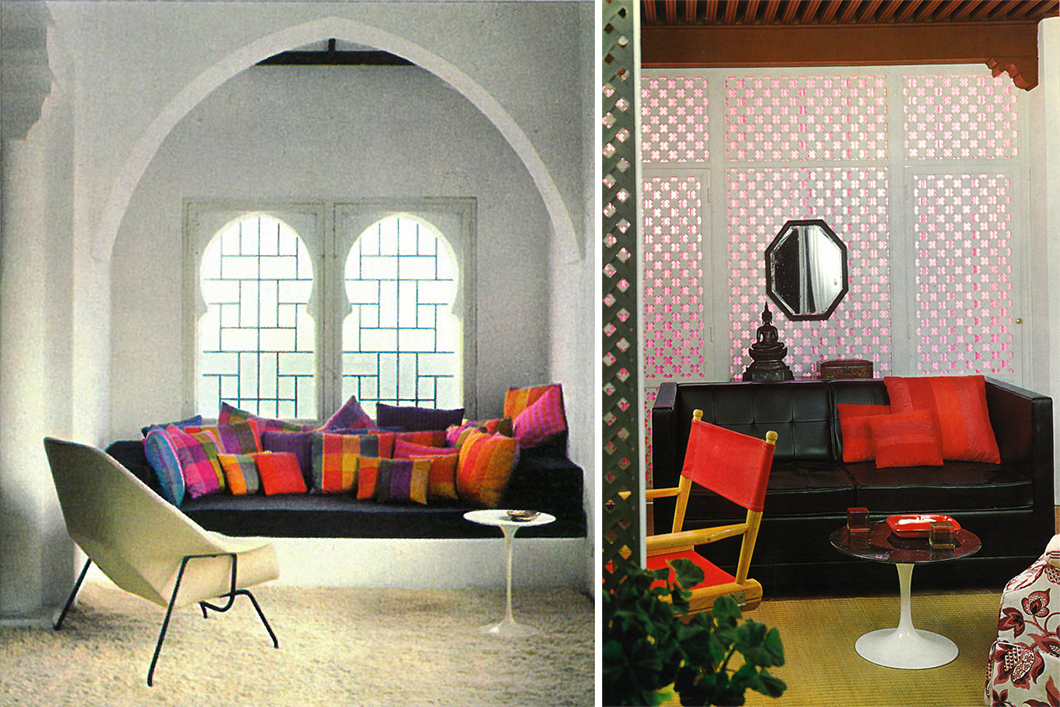

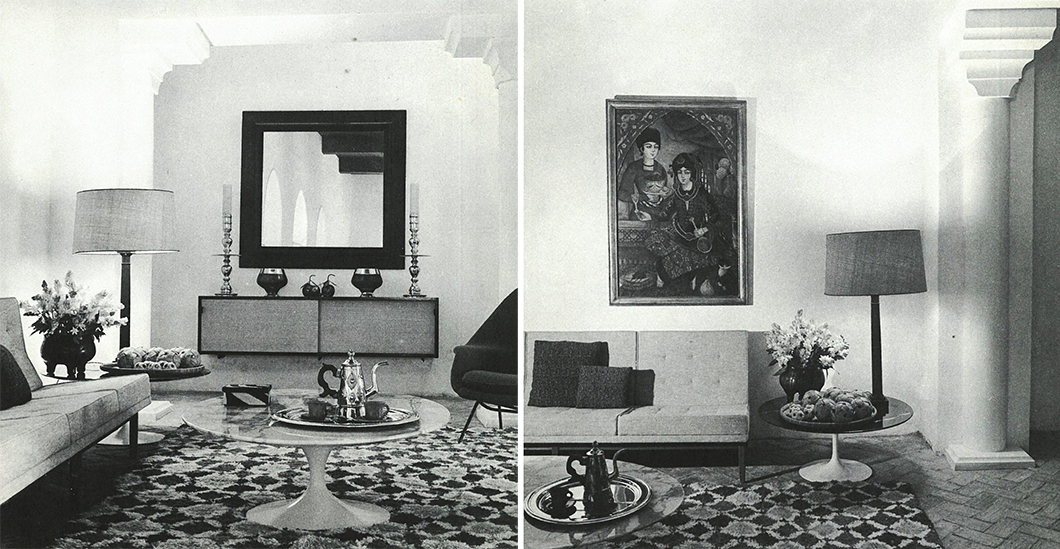

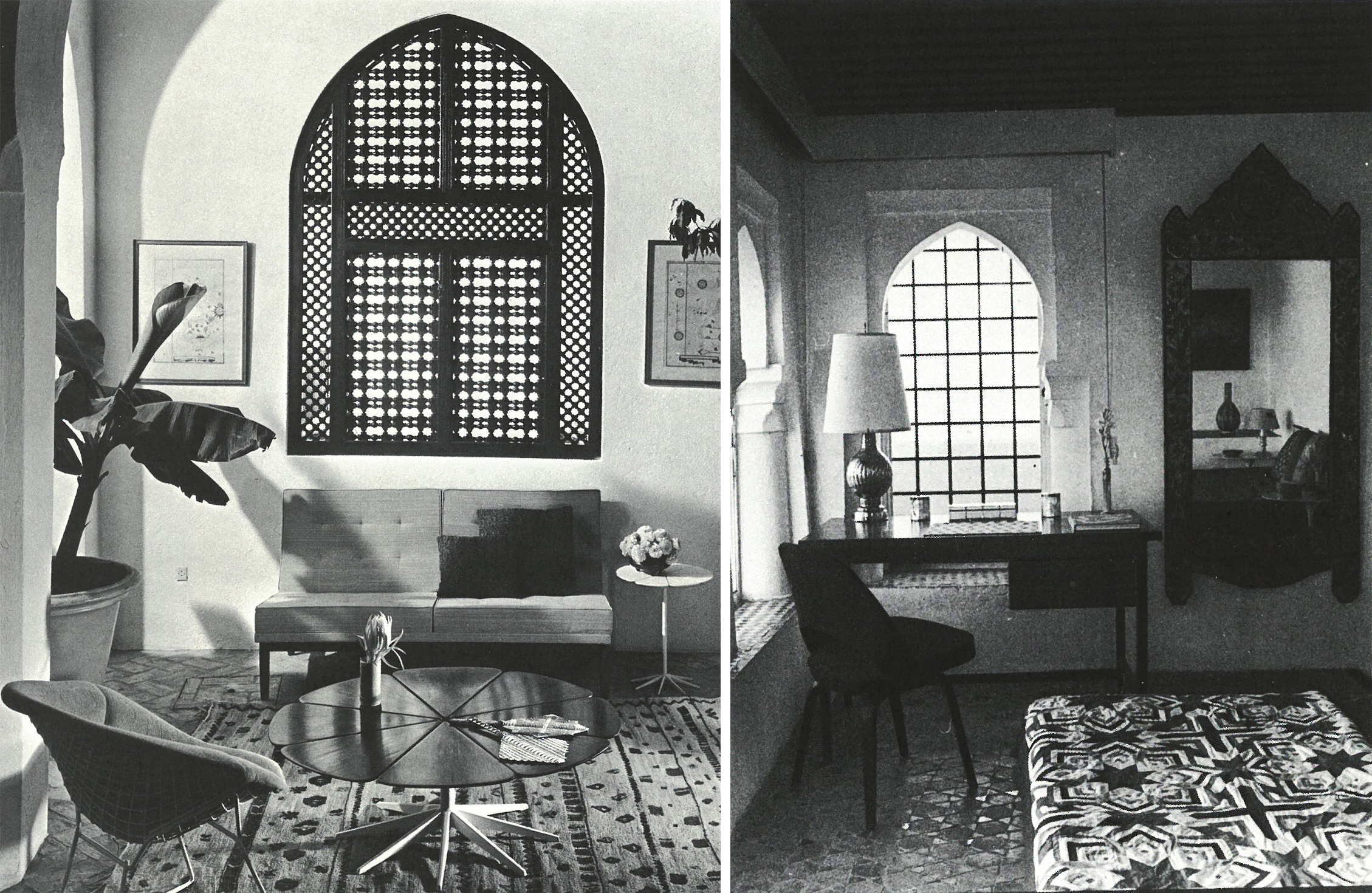

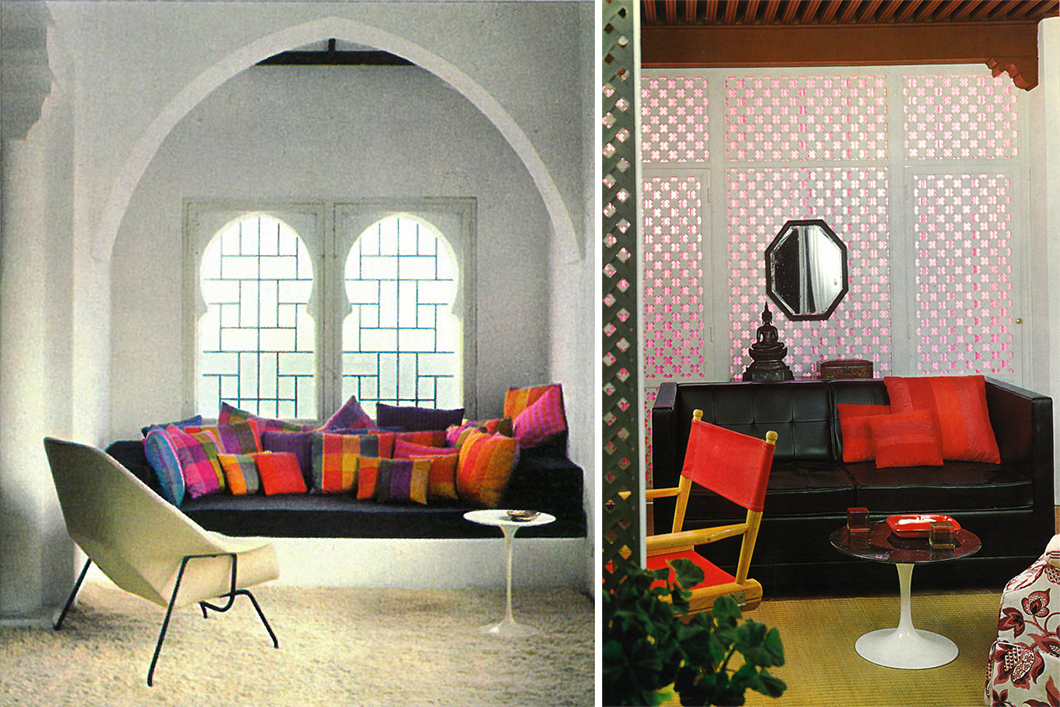

But while Vidal remained committed to the appearance of a past epoch, peppering his home with artisanal objects that added to an overwhelming orientalism, the furniture he selected adhered to principles of modernism that were nurtured at Knoll. And yet, the “stunning results” recalled by Parisian art magazine L’Oeil in 1962, proved “how happily contemporary design can be blended with traditional décor.” While the designs of Florence Knoll and Richard Schultz came from Knoll showrooms that were uniform in their modern visions, their presence in York Castle yielded a range of multifaceted scenes. The cool marble tops of Saarinen pedestal tables were scattered with local flowers, the delicate shadows cast by a wire Bertoia chair overlapped with those of latticed moucharabieh windows, the rich upholstery of Florence Knoll chairs paired well with the Thai silk pillows arranged upon them.

“The house in Tangiers was done about the early sixties,” Vidal recalled. “I think it showed people that you could mix it up with different furniture and objects and paintings which were not necessarily modern, it could be done with antiques.”

In the bedrooms and lounge areas, modern furniture was keenly balanced with oriental art and design.

Documenting the sumptuous abode, a feature in L’Oeil had much praise to bestow. “The smallest detail of furnishings reflects the purity of the architecture,” it noted. “The tables and chairs in the dining room, for example, seem to spring from the floor and incorporate themselves with the structure of the room. They do not give the impression of having been added but rather having evolved from the same architectural vein. Therein lies the magic of this Moorish-Portuguese castle, built in the 16th century, in which furniture created by the late architect Eero Saarinen in 1958, as well as by others, becomes an integral part.”

The terraces of York Castle offered ample room for sunbathing and dining en plein soleil.

Working outside in, Vidal created “a series of terraces so in keeping with the original architecture that they seem like ancient battlements,” according to L’Oeil. But a quick look at the decorative flourishes added to the outdoor spaces makes it clear that battle was the last thing they were meant for. Wicker beds with rubber mattresses were positioned in the sun to allow for afternoon tanning, while a row of columns framed an outdoor dining pergola complete with a Saarinen Pedestal Dining Table covered in fruit and wine.

The swimming pool and living room of York Castle boasted intricate patterns in rich blues and greens.

Entering the abode, visitors would encounter a range of screening elements that borrowed from the local vernacular, allowing dappled light to penetrate through windows and arches in different amounts. At the center of the castle was an octagonal courtyard open to the sky, enclosed by arcaded galleries on all sides. In the courtyard, Vidal built a swimming pool tiled with exact replicas of zelijes, a colorful hand-cut Moroccan tile, in a pattern that was repeated on a carpet in a corner of the castle’s living room. But in both places, the intricate diamond designs were contrasted against the crisp outlines of Knoll furniture, where the thin white stems of Saarinen’s Tulips and Schultz’s Petals found unlikely homes.

The main part of the 48-foot-long living room of York Castle, where Florence Knoll chairs were arranged around the fireplace.

Color and texture, it seemed, were definitive parts of the York Castle redesign. From the triangular cushions of Siam to the silver Persian flasks, the lounge areas of Vidal's home invited complete immersion into a blurry Oriental fantasy. Still, next to the Laotian war drums and Cambodian Buddhas stood the equally sculptural lamp designs of Isamu Noguchi, and below the geometric Tahitian textiles were the equally hypnotic lines of Bertoia Diamond Chairs. But while the endless artifacts of York Castle may have seemed indistinguishable in provenance, the Knoll designs among them joined in the exquisite amalgamation. Rather than evoke the poles of West and East, new and old, modern and traditional, the chairs and tables Vidal used to fill his home instead suggested an intercontinental affinity in design, tying together the craftsmanship of disparate places and times.

The colorful inner spaces of York Castle, where light filtered in through Moorish-inspired windows.

York Castle administered what was then a fresh dose of eclecticism, causing quite a stir back in Paris. As Vidal reflected, even the artificial spaces that Knoll put together in the French capital cut against every convention. “At that time, one big department store, Printemps, which is like Bloomingdales in New York, asked us to do a big exhibition,” he said. “It was a revelation for all the designers, architects, decorators. It was about 1954. It was the first time they saw tweeds on chairs, flowers put together the way we used to do it with very short stems. It was the first time they saw gravel on the floor, the first time they saw net on the windows, the first time they saw two colors close to each other like pink, orange and red; and blue and green. It was unheard of at the time, it wasn’t done. You couldn’t even put grey and beige together.”

The lavishly decorated living room of York Castle, where mint tea would be served on Saarinen Coffee Tables.

But the house in Tangiers defied the standards of the 1960s, becoming a symbol of luxurious living for an international cohort that would visit Tangier during the summer—and for those who could only hear of it from afar. In the process, as Vidal recollected, Knoll’s European audience made peace with the notion of inviting contemporary design into spaces bounded by tradition, oriental or not. “Little by little, it became absolutely chic to have Knoll furniture in your house,” he said.

Looking down one of the arcades around the central courtyard, lined with papyrus plants and Berber rugs.

All images from the Knoll Archive.

When Yves Vidal became the president of Knoll International in 1951, he inherited a company that had only recently upended the traditional idea of a furniture showroom. Under the direction of Florence Knoll, Knoll showrooms around the world were arranged as tableaus of habitable environments, a setup that was both confusing and alluring to visitors. At the Paris outpost, where Vidal first joined the company, the bewilderment was even more intensely felt.

When Yves Vidal became the president of Knoll International in 1951, he inherited a company that had only recently upended the traditional idea of a furniture showroom. Under the direction of Florence Knoll, Knoll showrooms around the world were arranged as tableaus of habitable environments, a setup that was both confusing and alluring to visitors. At the Paris outpost, where Vidal first joined the company, the bewilderment was even more intensely felt.